Making a game engine from scratch

Today we are proud to announce ‘Rubeus’! Rubeus is an open-source 2D game engine written purely in C++17 and is designed with a vision to inculcate the spirit of game development amongst the general public (specifically the IIT Roorkee junta). You can check out Rubeus at https://github.com/sdslabs/Rubeus.

What is a game engine? How is it different from a game?

A game engine, in its most mature form, is a platform that provides tools and utilities to game developers for designing and developing games based on their ideas.

To provide some comparisons, some of the most well-received games in the market have been Ubisoft games from the likes of the Assassin’s Creed franchise and the Watch_Dogs franchise. These games look and feel very similar to each other as both of these franchises have a stealth mechanic deeply rooted at their heart.

The stealth mode mechanic in Watch_Dogs 1 takes a whopping 100,000 lines of code in the game. It is not only economically impossible to regenerate and reintegrate that much amount of code for each and every game that gets released under the franchise, but would also take up a lot of the developers’ time. This is why Ubisoft has engraved the stealth mechanic in their game engine and they keep reusing it in their newer games with appropriate modifications.

Why make an entire game engine and not a game?

In reality, the development of most games at game studios starts with developing a game engine first. Creating a game without a game engine can be considered as hard-coding functionalities in a crude form. This means that if you happen to work on another project (perhaps a sequel of the previous game), you will have to again work on laying down the basic layer of functionalities that all types of games work on. It is likely that whenever you start working on a new project, a significant part of your code will be repeated every time. This practice of writing the same code every time you work on a new game is incredibly inefficient and this is a problem that we, at SDSLabs, intend to solve.

Making a game engine is a complex task and this is why most casual developers overlook the possibility of using a game engine to realize their game ideas. However, there are a lot of free alternatives out in the market. For example, you might have heard about Fortnite and the latest Tekken 7, both of which run on Epic Games Studio’s Unreal Engine 4. It has, in fact, made it possible for the Tekken franchise to finally hit the PC market. There are plenty of game engines out there but we decided to put ourselves up to the challenge of creating one for ourselves and releasing it to the public for everyone to use.

How to even start with making a game engine?

The starting days of Rubeus in the month of May 2018 were full of reading sessions. The best websites to look up information on topics that we found were related to game development are probably Gamedev.net and Gamasutra. We also recommend following r/gamedev on Reddit, which is a booming community of game developers from both indie and AAA studios.

The beginning of something amazing

One of the first hurdles that we faced was how we should implement the Rubeus engine’s architecture. We had zero levels of abstraction in our codebase and we were trying to create an API out of it that should be useful to even a newbie. This made us take a step back and we started to work on the individual modules of the engine rather than the API.

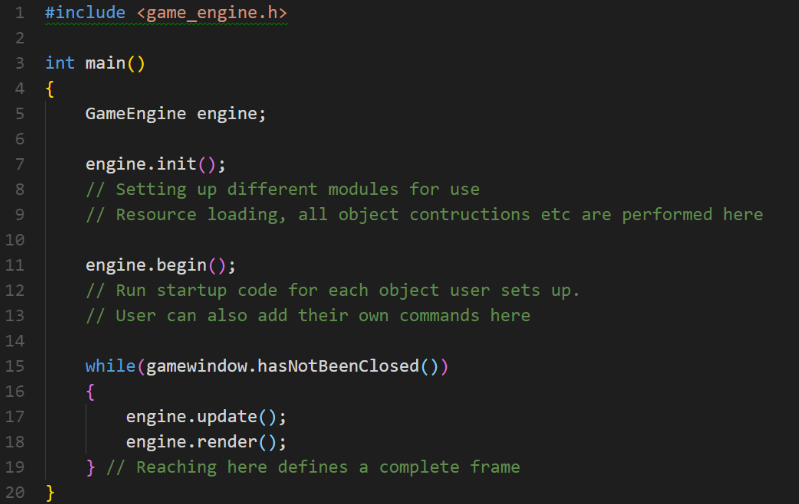

Any game engine works on a concept of what is known as the ‘Game Loop’. In the most general sense, games are recurrent programs. They do not normally shut down after their execution is complete. Instead, they often keep on repeating a particular set of instructions over and over unless the game shuts itself down or when the player has pressed the QUIT button. This is the concept of an ‘Application Loop’.

Now, let us see how game engines modify this concept so as to suit most closely to an actual game. A general game engine loop looks a bit like this:

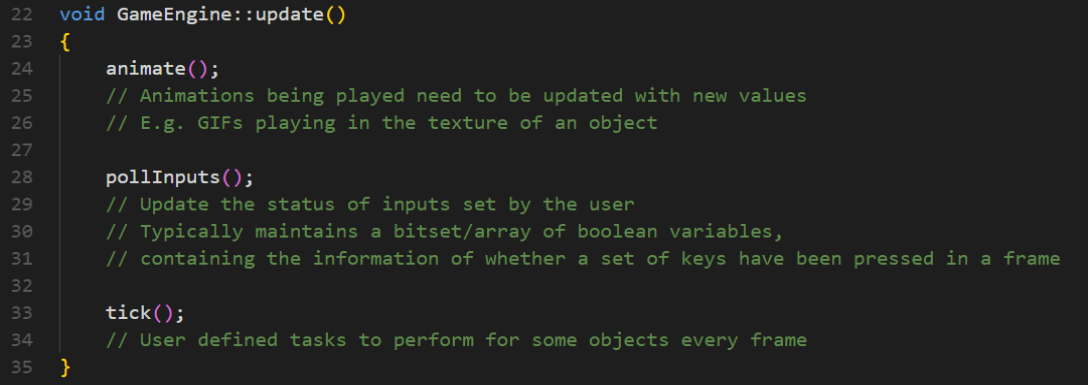

The engine update function above consists mainly of the physics engine update and the calling all the tick functions.

A tick function is some user-defined logic that the user wants to run at every frame in the game. It may contain all of the game logic or just a frame counter to measure the FPS. Coming to the physics engine update, it is also just a function that gets called once every frame but it checks for collisions every frame, and if it finds any collisions happening then it defines what change of velocities of the colliding game objects take place in that frame.

The most important parts of making a game engine are implementing the physics update function and the render function (also known as the drawing step). These two functions are implemented independently inside the physics engine and the rendering engine. The render function just renders the scene. It applies no game logic to the scene. All logic is covered inside the update functions. Render functions tend to take care of what visual effects the user requires at a certain moment in the game.

A typical single-threaded game engine update loop should look like this:

Taking all these bits of information together, we started building Rubeus function by function. We first listed down the basic components of a game engine. To give a gist of how and what we started to work on, below is some documentation on our process of building a game engine.

Graphics Components:

A window module that talks to the OS and generates a window which allows OpenGL drawings to be rendered on the screen

This had to be done in an OS-independent way because to keep the engine cross-platform. One such library that eases this task is GLFW(“OpenGL Framework”). GLFW makes the task of drawing to the screen independent of the OS using OpenGL completely hassle-free.

A rendering module that abstracts all objects appearing in the game with the specific image/color that they use to get rendered to the screen

It is also the renderer’s job to use the specific shaders that allow the objects to get colored in a way that the shader governs. In a nutshell, shaders are bits of code (written in OpenGL Shading Language a.k.a. GLSL, in our case) that tell the GPU where each vertex is present in the 3D space and what sort of algorithms should be used to color every pixel along with what sort of effects should be applied to the rendered image.

For example, 3D games nowadays have started using a ‘Bloom’ effect to highlight bright objects on the screen.

Bloom effect is a lighting illusion that is used to make objects appear brighter than the maximum brightness of the monitor.

This particular effect i.e. Bloom effect is implemented inside shaders and the renderer uses these shaders to output graphics on the screen.

During the development of Rubeus’ renderer, that we proudly named the ‘Guerrilla Renderer’, we ran a benchmark at rendering 14,560 sprites (a.k.a. 2D objects) at 450 FPS on a GTX 1060 (6GB). We tried to crank the numbers higher and somehow managed to choke our own engine by displaying 122,300 sprites at 4 FPS. A quick reminder: No real-life game ever reaches these numbers of objects being displayed at a time. We had also tested Guerrilla only in Debug mode without any form of inlining of C++ code.

This is a test run from another benchmark that we ran.

Multithreading:

We were aware of the fact that even if we may not ever make Rubeus multithreaded in the first place, we may require the need to perform asynchronous responses such as implementing a console, or a debug menu for the user that use Rubeus to make a game for their players.

Multithreaded programs are exactly what they sound like. They are able to follow more than 1 flow of execution of code at a certain moment in time. Beware that such systems can be incredibly hard to build because improper sharing of resources and also just overuse of threading will also give a negative hit to the performance of the engine.

We have implemented a multithreaded messaging system inside Rubeus that we plan to release in v2.0. More information on this type of an architecture can be found in this wonderful article about making different types of game engine architectures.

By the time we were done with the multithreading architecture and the Guerrilla renderer, it was already mid-July and we had started to realize that this project might take a while to get completed. Not because of any lack of development times but the sheer size of this project. It was about time we started to really speed things up or Rubeus would be seeing the light of the day not before 2019 or maybe even not at all.

A Physics Engine:

Rubeus’ physics engine, nicknamed ‘Awerere’ (pronounced as “auror”) is also what it sounds like. Awerere is a physics engine that works inside Rubeus and allows simulation of life-like collisions and physics of game objects.

The physics engine is an essential part of bringing any form of realism in a game. It is responsible for figuring out what objects are colliding with each other, what objects are not colliding with each other and if they are colliding, what velocities do they move away with and if they have collided, should they repel like rigid bodies or do they release some form of energy (likes of what we see in inelastic collisions amongst rigid bodies).

All these questions are what the physics engine has to find the answers for. Sometimes the user can define some customized response to collisions. For example, the user would like to open a door to another doorway if the player shoots a particular switch on the wall.

Currently, Awerere supports shapes such as boxes, circles, and planes. It handles collisions amongst all of the permutations of these objects and assigns them their final physical state after the collision. Designing Awerere and implementing the different collision algorithms was a treat because we personally like studying and realizing rigid body physics with the help of real-world physical laws.

Inputs and Sounds Manager:

In this part of the development cycle, we were slowly approaching the release date and we had already implemented and debugged the hard parts of implementing a physics engine.

We have used the popular ‘Simple and Fast Multimedia Library’, often known as just ‘SFML’ to provide Rubeus with cross-platform access to the sound devices in an organized sound manager. Rubeus now supports loading both long audio tracks like ambient and background music in addition to short pieces of audio like footsteps, gunshots, etcetera.

When we had selected GLFW for generating windows on all OSs, we also had to keep a note of how GLFW handled getting inputs from the input devices. It also provides keyboard presses along with mouse button presses, scrolling, and just plain cursor positions. But all of this is done in an asynchronous response that GLFW provides the engine. We have implemented a system that keeps track of what keys have been pressed and what keys have been released at the starting of every frame. This made up the base of creating the Input manager which we further abstracted to work by creating keybindings for each control. Multiple keys are now assignable to a single keybinding/control.

Bringing everything together

Near the end of November we were ready with all subsystems and modules that were required to make up Rubeus. But we still did not have an API or a gateway that the user could interact with.

This is when we came up with broCLI, which stands for ‘Rubeus on Command Line Interface’. broCLI is a CLI tool implemented in Golang which helps create a project structure for Rubeus. It was the perfect idea for Rubeus to use a CLI tool instead of a GUI so that users get a feeling of doing some heavy work while working with Rubeus. The user persona for Rubeus was always a beginner programmer from the start of May 2018. A CLI is probably something that they will be seeing a lot in their coming days.

Rubeus may have a GUI later but for v1.0, we are focusing only on a CLI.

Fast forward to this day

We are happy that we were able to implement such a complex piece of technology with elegance and now, we invite others to partake in this endeavor into the realms of game development.

If you are interested in game engineering then you are more than welcome to help us take Rubeus further and contribute to the project. Otherwise, please have a stop by at the Github repository https://github.com/sdslabs/Rubeus and try to make something amazing with it. We will be honored to see you create something beautiful with Rubeus and we look forward to your support.

P.S. We maintain a public list of awesome projects that we find to be built on Rubeus. You can be featured on it too!